The sublime is not in the mountain, nor in the storm, but in the tremor of the heart that recognises its own vastness reflected there.

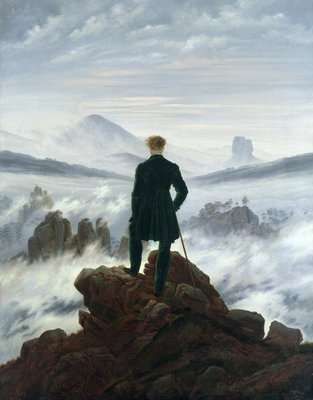

A lone figure stands at the crest of a mountain. He gazes across a sea of mist, calm and steady, while we – the viewers – stand safely just below the summit, invited to contemplate the vastness of it all. Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818) is one of the most enduring images of Romanticism: human smallness set against the immensities of nature.

Yet what strikes us most is not the mountain itself, but the figure. We never quite see the view as he sees it. Our gaze returns, again and again, to the back of his coat, his hair caught in the wind. We remain tethered to the human.

Philosophers remind us that this tether matters. Immanuel Kant drew a distinction between the beautiful and the sublime. Beauty, he argued, belongs to form – a flower, a tree, a calm lake, proportioned and pleasing. The sublime is different: it overwhelms, it resists containment. The sublime is not in the storm or the mountain but in the imagination they stir. It is the trembling sense that we are meeting something larger than ourselves, and that we cannot fully hold it.

By this measure, Friedrich’s painting keeps us from the truly sublime. The wanderer steadies the scene. His presence grants us safety, a reference point. What might have dissolved into boundless terror becomes navigable, almost serene.

And yet, Friedrich himself once advised:

“Close your physical eye, so that you may see your picture first with the spiritual eye. Then bring what you saw in the dark into the light.”

The sublime, he knew, is never just “out there” in the mountains or seas, but also “in here,” in the imagination that meets them.

The Sublime as Presence

To encounter the sublime is to feel, if only for a moment, that the boundaries of the self have dissolved into something larger – a horizon, a silence, a sky. It is not far from what we now call mindfulness: a release of striving, a letting-go into what simply is.

The poet Christian Bobin captured this paradox in the simplest of gestures:

“I was peeling a red apple from the garden when I suddenly understood that life would only ever give me a series of wonderfully insoluble problems. With that thought, an ocean of profound peace entered my heart.”

The sublime does not arrive only on mountaintops. It arrives in kitchens, in gardens, in the smallest overlooked moment.

When the World Breaks Through

Since the eighteenth century, nature has been measured, mapped, subdued. Yet what is repressed always returns. Literary scholar Jonathan Bate called the sublime a “shiver of delight” – nature breaking through the structures of rational control.

George Orwell, with his plain clarity, defended the right to notice beauty even amidst political turmoil:

“Is it politically reprehensible… to point out that life is frequently worth living because of a blackbird’s song, a yellow elm tree in October, or some other natural phenomenon which does not cost money?”

Such moments, however small, resist reduction. They remind us that life is not only useful but luminous.

The Work of Imagination

Yuval Noah Harari describes the “Cognitive Revolution” as the birth of a dual reality: one of rivers, trees, animals, and another of gods, symbols, and stories. Imagination, he suggests, is what allowed us to change quickly, to transmit behaviour across generations, to dream futures into being.

Carl Jung went further.

“The great joy of play, fantasy and the imagination is that for a time we are utterly spontaneous, free to imagine anything. In such a pure state of pure being, no thought is unthinkable.”

For Jung, imagination was not an escape but another form of reality – a cauldron of symbols and wisdom, just as real as the world of stone and soil. To live without imagination is to live only half a life.

The Living World

Nature exceeds us, yet it also includes us. Philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty once said, “There is a style of being.” Each creature, each tree, each stone carries its own particular presence. Poet Louis MacNeice echoed: “The only invulnerable Universal is one that is incarnate.”

The word human itself comes from humus – the soil. To be human is to be of the earth.

This is why encounters with wild lives can feel like enchantment. Horatio Clare once described being “bewitched” by the sheer presence of a red grouse, as though the entire morning reorganised itself around the bird. Such encounters remind us that the world is alive – not backdrop, but participant.

Toward the Unknown

Imagination is the bridge between inner and outer, between what is visible and what is hidden. It gathers fragments of past, present, and future into meaning. It also draws us forward, toward what we do not yet know.

William Blake once wrote: “Great things are done when men and mountains meet.” For him, as for Friedrich, mountains were not just rock and ice but myth, interior visions rising from the mist.

And Friedrich himself confessed that it is often the hazy, the half-seen, the veiled that stirs us most:

“When a scene is shrouded in mist, it seems greater, nobler, and heightens the viewers’ imaginative powers… The eye and the imagination are more readily drawn by nebulous distance than by what is perfectly plain for all to see.”

Perhaps that is the essence of the sublime. Not the mountain, nor the storm, nor even the painting itself – but the imagination it awakens in us. The reminder that we are both soil and spirit, both finite and infinite, both the wanderer and the fog.

Perhaps the greatest sublime is not in the storm or the peak, but in the simple fact that we are here at all. Alive, breathing, brief. The mist will lift. The question is how we choose to live before it does.

Leave a comment