On Blake, Eliot, Jung, and the ancient necessity of wonder

We live in an age of explanations – of graphs and headlines, of causes and consequences neatly arranged. Yet beneath this craving for mastery lies a quieter truth: the world does not ask to be explained so much as it asks to be wondered at. Across centuries, philosophers and poets – from Descartes to Goethe, from Blake to Eliot – have circled back to the same intuition: that astonishment at being is not a distraction from life, but its essence.

This essay is a meditation on that astonishment – on wonder as both the origin and aim of philosophy, on nature as the muse and mirror of imagination, on the fragile courage of creation, and on the everyday enchantments that tether us to the eternal. From the hush after rain to the vastness of a mountain fog, from a blackbird’s song to a red grouse lifting into morning air, it invites us to return to what Eliot called the “still point of the turning world” – that space where time falls away and there is only the dance.

“All philosophy begins in wonder,” Plato observed more than two millennia ago – a sentiment echoed by thinkers across centuries, as if to remind us that astonishment at being is not a luxury but a necessity.

Descartes, who once tried to build the entire cathedral of knowledge on the firm foundation of doubt, nonetheless conceded that wonder is “the first of all the passions.” Goethe, that great celebrant of metamorphosis, went further: wonder, he thought, is “the highest that man can attain.” And Wittgenstein – who spent his life dismantling the scaffolding of pseudo-explanations – believed the role of philosophy was not to resolve mystery but to deepen our receptivity to it, “to make way for wonder.”

And yet – wonder is the easiest thing to misplace in the bustle of modern life, so easily drowned in the daily deluge of information and urgency. We scroll, we schedule, we solve. But we do not wonder.

Still, wonder waits.

Sometimes it returns in the form of a blackbird’s song outside the window, breaking through the noise of a morning already crowded with tasks. Sometimes it is the sudden flare of a beech tree in October, its canopy turned to a fleeting blaze of copper light, reminding us that time is not just a measurement of hours but a cycle of beauty. Sometimes it is the nearly invisible body of a hovering insect, delicate as breath, which appears from nowhere and seems to carry the secret of existence in its fragile wings.

These moments are not digressions. They are the marrow of life. They remind us that philosophy is not, at its heart, a system of arguments but a state of attention – a way of standing astonished before the simple fact that anything exists at all.

The Still Point

T.S. Eliot, in the first of his Four Quartets, named a place he called “the still point of the turning world.”

“Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.”

It is a paradox – the unmoving center around which all movement circles, the silence without which no sound would be possible. It is not fixity, and not flux, but something prior to both – the point of pure potentiality.

In shamanic traditions, this would be called the void – not emptiness in the sense of lack, but the fertile nothingness from which everything arises. The physicist might reach for similar metaphors when speaking of the quantum vacuum, that strange plenum in which particles flicker into being and dissolve again. Across languages of myth, poetry, and science, the intuition is the same: behind the constant turbulence of becoming, there is a depth of stillness that is never touched.

We glimpse this still point rarely, and never for long. It comes unbidden – sometimes in the hush that falls just after rain, sometimes in the quiet moment before a bird takes flight. For an instant, time loosens its grip. The mind stops rehearsing past and future. We find ourselves in the naked present, and it feels like eternity.

Schelling, writing in the nineteenth century, called this capacity the most marvelous in us: the ability to draw back “from the stream of time … into our innermost being and there, in the immutable form of the Eternal, to look into ourselves.”

Perhaps this is the truest meaning of philosophy, and of art: not the construction of systems, but the cultivation of this inner pause. A way of returning, again and again, to the still point where the world shows itself as wonder.

Blake’s Double Vision

For William Blake, Nature was never innocent. He saw in it the evidence of humanity’s Fall – the descent into matter, into time, into the realm of things that are born and die. “Everything in Nature,” he wrote, “has a birthdate, a duration, and an expiration date.” To live only in nature was, for him, to live cut off from the eternal.

And yet Blake, who distrusted Nature as veil, also loved it as muse. He could not resist its beauty, nor deny its power to awaken the imagination. “To the eyes of the man of imagination, nature is imagination itself,” he wrote.

Here is Blake’s contradiction, which may also be ours. Nature is temporary – leaves falling, rivers changing course, lives beginning and ending. And yet Nature is also eternal, for it carries us beyond itself: the copper flame of a beech tree in autumn, the cry of a curlew across the estuary, the sudden shimmer of dragonfly wings. Each moment is passing; each is also a doorway.

Blake knew that imagination was the bridge. The tree that is “only a green thing in the way” to one person may to another be a revelation, capable of moving them to tears. The difference lies not in the tree but in the eye that sees. “As a man is, so he sees. As the eye is formed, such are its powers.”

We live, then, in two worlds at once. One is temporal, where things fade. The other is eternal, where imagination transfigures what it touches. To walk among trees is to walk in both worlds. The bark and leaf belong to time, but the symbol they awaken in us belongs to the timeless.

It is in this double vision – Nature as fallen matter, Nature as eternal muse – that Blake locates the possibility of art. From the friction of the two comes fire.

The Fragility of Creation

Blake’s paradox – that imagination both depends upon nature and yet exceeds it – echoes through art and philosophy in subtler ways. Creation itself, it seems, always carries a tension between possibility and paralysis.

No figure embodies this tension more poignantly than Hamlet. He knows what he must do. He knows the story he is caught within, the duty expected of him. And yet, when he stands alone in the half-light of his soliloquies, he hesitates. “To be, or not to be” is not just a meditation on life and death; it is a meditation on action and inaction, on the gulf between knowing and doing.

Hamlet’s imagination is both his genius and his undoing. He can picture every consequence, every hesitation, every alternate path – and so he is paralysed by them.

The artist knows this paralysis well. To begin a work of art is to confront a void. Out of nothing, something must come. And in that gap, fear rushes in.

This fear has long been mythologised. We tell ourselves that creativity is inherently bound to suffering. We recite the biographies of van Gogh, of Plath, of countless others, as if to prove that artistic genius exacts its toll in anguish. Norman Mailer once confessed, “Every one of my books killed me a little more.” We nod, hardly surprised, as if art must always wound its maker.

But what if this is less truth than story – a story we have rehearsed so long we mistake it for law? What if creation, at its core, is not about suffering at all, but about returning to wonder?

To create is to stand again in the still point – to touch that space where imagination transfigures the temporal into the eternal. It is not depletion but replenishment. Not death by a thousand cuts, but life renewed by a thousand glimpses of astonishment.

The fragility of creation, then, is not that it kills us. It is that it requires us to stay tender enough to wonder, and brave enough to bring that wonder into form.

Enchantment in the Everyday

If creation is a return to wonder, then its raw material is often found in what seems, at first glance, too ordinary to notice.

George Orwell once asked whether it was “politically reprehensible” to take delight in the small, uncommodified beauties of the world – the song of a blackbird, the autumn fire of a tree – while society groans under economic and political burdens. He knew that some would see such joys as trivial, even irresponsible, because they lack what newspapers call “a class angle.” But to deny their worth is to deny the very marrow of being.

The Norwegian poet Hans Børli captured this truth in a single scent. The smell of freshly cut wood, he wrote, is “sweet and naked… as if life itself had walked by you, with dew in its hair.” He believed it would be one of the last things a person ever forgets.

Such experiences – a blackbird, a wood’s fragrance, the sudden brilliance of a beech tree – do not need to be rare or grand to be transformative. They are thresholds. They remind us, in an unassuming way, of the immense gift of being alive.

And they mark us more deeply than we know. The landscapes of childhood – the bend of a river, the angle of light in winter, the particular birdsong of our first years – sink into us as lifelong benchmarks. Long after we forget names or dates, these impressions remain. They form a kind of inner weather, a climate of memory against which all later seasons are measured.

To notice such things is not escapism. It is enchantment in its most radical form – the insistence that life is worth living not only for its crises and its conquests, but for the grace of a bird’s flight, the curve of a branch, the smell of wood on a cold morning.

To see the world in this way is to allow imagination and reality to meet in quiet daily acts of wonder. It is to understand that meaning need not be manufactured; it is already present, waiting in the ordinary.

The Sublime and Its Shadows

If the everyday offers us small doorways into wonder, art and philosophy have long sought to widen those thresholds into something vaster – what Immanuel Kant called the sublime.

“The beautiful,” Kant wrote, “is limited.” It charms, it soothes, it pleases. “But the sublime is limitless” – it leaves us standing before something our imagination cannot encompass. The mind stretches toward immensity, fails, and yet takes strange pleasure in the attempt.

This is the grandeur of mountain ranges, of night skies spangled with stars, of seas that thunder against rock. It is awe mixed with fear, a reminder of nature’s scale and our smallness within it.

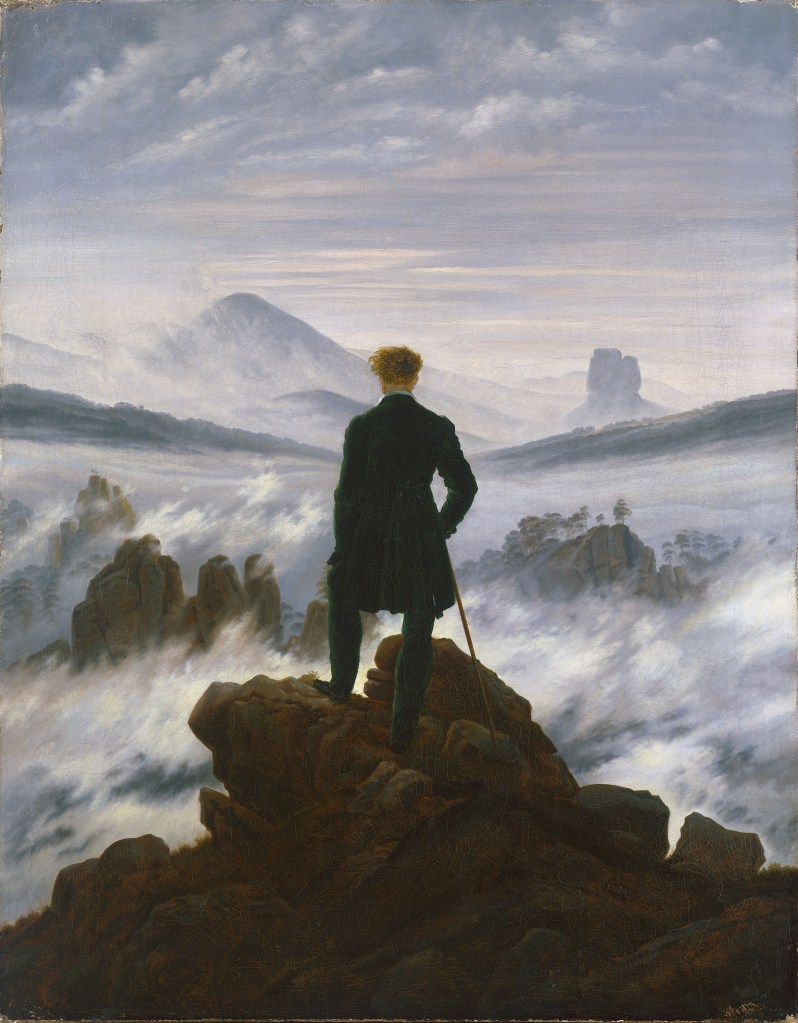

Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog has become an emblem of this experience. A lone figure stands on a rocky summit, his back to us, gazing into a landscape half-concealed by mist. Peaks rise and vanish into the haze. The scene feels at once infinite and uncertain – the path ahead veiled, the future unreadable.

And yet, on closer look, Friedrich’s painting does not confront us with terror. It does not overwhelm us as a hurricane or avalanche might. Instead, it invites contemplation. The figure anchors the scene, reminding us that what matters is not only the vastness of the view but the act of beholding it.

Friedrich himself urged: “Close your physical eye, so that you may see your picture first with the spiritual eye.” Art, in this sense, is not a mirror of nature but a companion to it – a way of sharpening our inner sight so that we may glimpse more deeply into what already surrounds us.

The sublime, then, need not annihilate. It can also console. It can remind us that beyond the reach of reason and explanation lies a deeper seeing: the awareness that the fog itself is part of the mystery, and that mystery is not a problem to be solved but a reality to be lived with.

In this gentler form, the sublime becomes less about fear of our smallness than about reverence for the vastness we are part of. It is another mode of wonder – not the fragile astonishment of the everyday, but the expansive awe of the infinite.

The Reservoir of the Unconscious

Carl Jung believed that no one lives entirely within their own psychic shell. However solitary we may feel, we are joined by what he called the collective unconscious – “that immense treasury, that great reservoir from which we draw.” In one of his later letters, he went further: the collective unconscious, he wrote, is “identical with Nature to the extent that Nature herself, including matter, is unknown to us.”

To turn toward nature, then, is also to turn inward. The mystery of a woodland pool, the silence of a moor at dusk, the glimmer of starlight on water – these are not only external events but inner ones. They awaken in us patterns older than memory, resonances formed long before we were born.

The philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty spoke of this as “a style of being.” Each living thing, he suggested, is not generic but particular: it has its own presence, its own manner of existence. The poet Louis MacNeice echoed this when he wrote that “the only invulnerable Universal is one that is incarnate.”

To encounter another being – a grouse rising in sudden flight, a fox slipping between hedgerows, even the fragile hovering of an insect – is to meet not an example of a species but a presence. Horatio Clare once remembered being “bewitched” by a red grouse, the bird’s sheer being somehow rearranging the morning around it.

Such moments of enchantment are not unlike falling in love. Something larger than reason breaks through; explanation falls away. We are left with presence alone, raw and unmediated.

In these encounters, we glimpse Jung’s truth: that nature is not separate from us but continuous with us – a mirror of the unknown depths within. To stand before a bird, a tree, a stone, is to stand also before the mystery of our own being.

The Dance

We have followed wonder across many thresholds – from Eliot’s still point to Blake’s double vision, from Hamlet’s paralysis to the fragile courage of creation, from the everyday enchantments of birdsong and woodsmoke to the sublime vastness of mist and mountain, from Jung’s reservoir of the unconscious to the living presence of a grouse rising into morning air.

What binds them all is not explanation but attention.

We live in a culture that prizes mastery – mastery over matter, over mind, even over nature itself. But victory in such a battle would be a hollow one. To conquer nature is to conquer ourselves, and in that triumph there would be only silence. Not the stillness of the eternal, but the stillness of absence.

Civilisation, if it is to be sane, must be something else: not conquest, but accommodation; not dominion, but celebration. Such a way of life would not itself be enchantment, but it would leave space for enchantment to occur.

And enchantment is what keeps us human.

To remain awake to the world – to the beech tree’s brief autumn fire, to the insect’s impossible hovering, to the red grouse that “made the morning surround him” – is to remember that we, too, belong to this dance.

Eliot was right: there is only the dance. The task is not to explain it away, nor to withdraw from it, but to join it with attention and reverence. To be astonished that there is something rather than nothing, and to let that astonishment guide how we live.

In the end, wonder is not a passing mood. It is the still point itself – the silent pulse that makes the turning world possible. And in every act of noticing, every gesture of imagination, we step once more into the dance.

To wonder is not to escape the world, but to enter it more deeply – to stand in the still point where the fleeting becomes eternal, and to remember that we are part of the dance that makes the world alive.

Further Reading

- T.S. Eliot – Four Quartets: A meditation on time, stillness, and the eternal.

- William Blake – The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: Visionary reflections on imagination and nature.

- Iain McGilchrist – The Master and His Emissary: On the divided brain, culture, and the necessity of wonder.

- George Orwell – “Some Thoughts on the Common Toad”: A defense of ordinary enchantments amid political struggle.

- Robin Wall Kimmerer – Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom and scientific insight woven into a hymn to reciprocity.

- Robert Macfarlane – The Wild Places: An exploration of Britain’s landscapes as sources of awe and renewal.

Leave a comment