A long-read reflection for a quiet weekend morning.

There are as many ways of seeing the world as there are eyes to see it. Yet, some patterns repeat themselves across cultures and centuries – archetypal lenses through which we make sense of life. Rudolf Steiner, the Austrian philosopher and educator, devoted years of research to understanding these different “worldviews.”

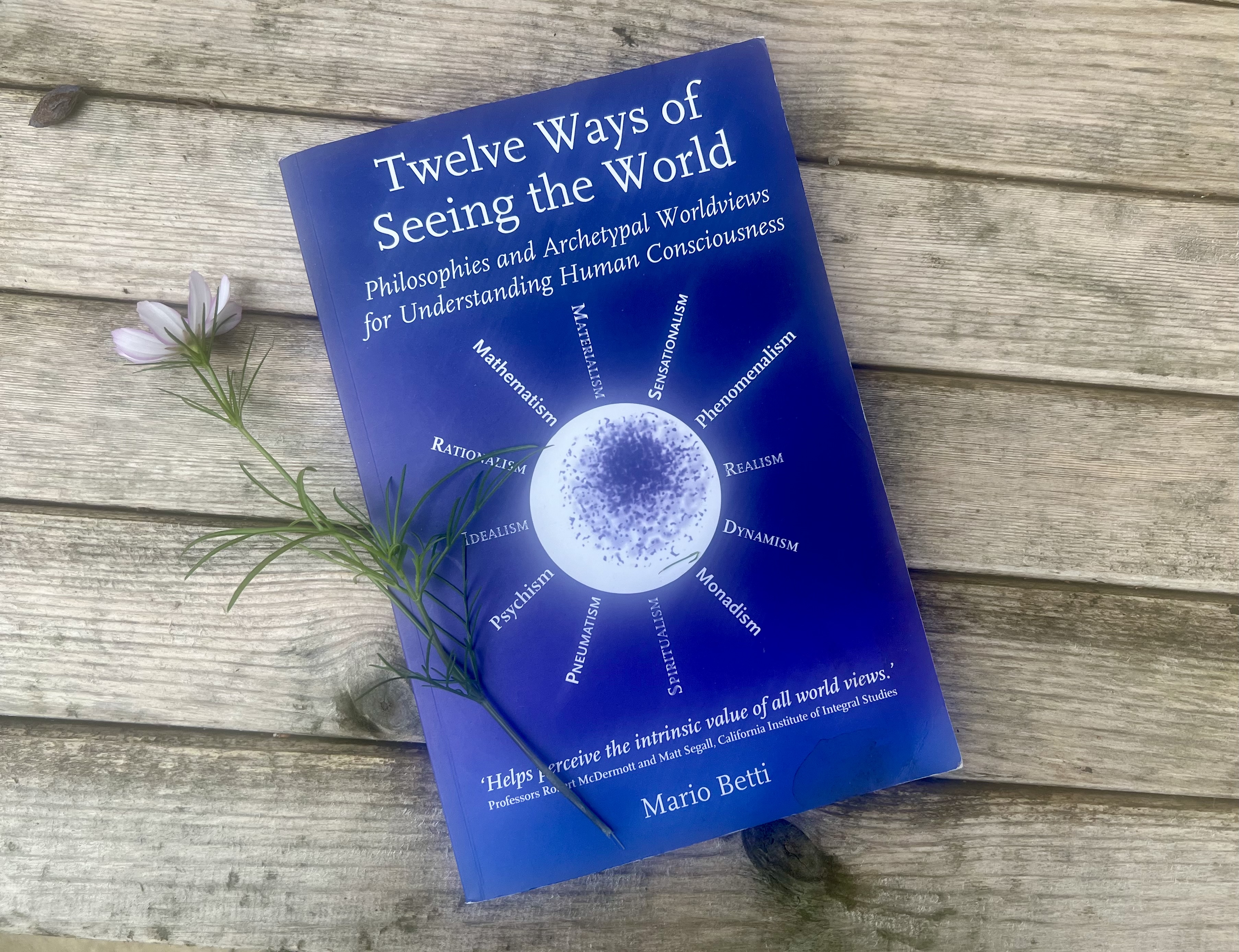

In his work, later explored beautifully in Mario Betti’s book The Twelve Ways of Seeing the World, we find a map of twelve archetypal perspectives on reality. Betti describes them not as rigid boxes, but as complementary approaches to truth – each carrying a fragment of wisdom, each incomplete on its own. His aim is not to declare one superior, but to help us transform dogmatism into dialogue and curiosity.

The 12 Worldviews

The following archetypal lenses, described by Steiner and elaborated by Betti, are like facets of a gem – each reflecting a different glimmer of reality:

- Phenomenalism: Focuses on the appearance of the world to our senses.

- Sensualism: Regards sensory experience as the basis of all knowledge.

- Materialism: Views matter as the fundamental reality, reducing everything to material principles.

- Mathematism: Emphasises mathematical principles and relationships in understanding the world.

- Rationalism: Prioritises reason and logic as the source of knowledge.

- Idealism: Posits that reality is fundamentally mental or conceptual, often rooted in ideas.

- Psychism: Explores the inner experience of the “I,” focusing on self-perception and introspection.

- Pneumatism: Relates to spiritual experience and gnosis, asserting a connection with the universe.

- Monadism: An outlook that explores fundamental units of reality.

- Dynamism: Focuses on the forces and energies that shape the world.

- Realism: Asserts the independent existence of things outside the mind.

- Humanism: A perspective that seeks to understand the world through human experience and potential.

As Betti explains, we each tend to favor a few of these lenses. A mathematician may lean toward mathematism; a mystic, toward pneumatism; a biologist, toward realism or dynamism. But life invites us to soften our allegiance to any single lens and learn from the others.

Seeing Nature Through Many Eyes

This is where the connection with nature becomes vivid.

When we walk into a forest, we might first see it materially – trees, soil, water, nutrients. Another day we may be struck by its dynamism – wind moving through branches, unseen forces shaping life. At dusk, we might feel pneumatism – a sense of sacred presence in the hush. Through humanism, we reflect on our place within this web. Each lens shifts what we notice, what we value, how we care.

The purpose of exploring these perspectives is not to adopt them all at once, but to recognise the richness they bring when held together. As Betti writes, understanding complementarity fosters empathy – both with those who see differently from us and with the living Earth herself.

Nature, too, thrives on diversity. A meadow does not ask every flower to be the same. The ecosystem flourishes because of variety, tension, and interdependence. Might we learn to see the world – and one another – with that same generosity?

Steiner suggested that our task as human beings is to widen our consciousness so that no single truth hardens into an idol. When we do, dialogue deepens, and responsibility grows. For the more ways we see the world, the more we realise how deeply we belong to it – and how tenderly it depends on us.

This weekend, perhaps take a walk and ask yourself:

- Which lens am I looking through right now?

- What might I notice if I shifted my perspective, even briefly?

- Which ways of seeing might invite me to care more deeply for the Earth, and for each other?

As the poet Rilke wrote: “Try to love the questions themselves… Live the questions now.”

The twelve ways of seeing are not answers. They are invitations – to curiosity, compassion, and wonder. And in that, they open a doorway to the wild mind of the world.

About Mario Betti:

Mario Betti is an Italian philosopher and educator who has devoted his work to making Steiner’s spiritual-scientific insights accessible and practical. His book The Twelve Ways of Seeing the World offers a path toward understanding and complementarity, helping transform dogmatic thinking into dialogue – within ourselves and with others.

For those wishing to wander further…

If this exploration stirs something in you, you might enjoy wandering further into the thinkers who have explored these questions of perspective and perception. Mario Betti’s The Twelve Ways of Seeing the World is a gentle doorway into Rudolf Steiner’s original research, showing how these twelve archetypal lenses can soften dogmatism and open dialogue. To deepen the philosophical thread, Steiner’s own lectures on worldviews and human consciousness offer a glimpse into the spiritual-scientific foundation from which Betti draws. For those drawn to poetry and attention, the works of Mary Oliver and Rainer Maria Rilke remind us how language itself can shift the way we see; their words invite a phenomenological gaze, noticing the world as it appears and transforms us. And if you long for a modern voice, Iain McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary offers a profound meditation on how our brain’s hemispheric ways of knowing shape culture, while David Abram’s The Spell of the Sensuous restores our felt connection to the animate Earth. None of these texts need to be read in order or in full; they are companions rather than assignments. Each, in its own way, invites us to pause, tilt our head, and ask: What else is here, waiting to be seen?

Leave a comment